I wanted to respond to several insightful comments on

my recent post on power laws in finance. And, after that, pose a question on the economics/finance history of financial time series that I hope someone out there might be able to help me with.

First, comments:

I actually agree with these statements. Let me try to clarify. In my post I said, referring to the fat tails in returns and 1/t decay of volatility correlations, that "None of these patterns can be explained by anything in the standard economic theories of markets (the EMH etc)." The key word is of course "explained."

The EMH has so much flexibility and is so loosely linked to real data that it is indeed consistent with these observations, as Ivansml (Mark) and James rightly point out. I think it is probably consistent with any conceivable time series of prices. But "being consistent with" isn't a very strong claim, especially if the consistency comes from making further subsidiary assumptions about how these fat tails might come from fluctuations in fundamental values. This seems like a "just so" story (even if the idea that fluctuations in fundamental values could have fat tails is not at all preposterous).

The point I wanted to make is that nothing (that I know of) in traditional economics/finance (i.e. coming out of the EMH paradigm) gives a natural and convincing explanation of these statistical regularities. Such an explanation would start from simple well accepted facts about the behaviour of individuals, firms, etc., market structures and so on, and then demonstrate how -- because of certain logical consequences following from these facts and their interactions -- we should actually expect to find just these kinds of power laws, with the same exponents, etc., and in many different markets. Reading such an explanation, you would say "Oh, now I see where it comes from and how it works!"

To illustrate some possibilities, one class of proposed explanations sees large market movements as having inherently collective origins, i.e. as reflecting large avalanches of trading behaviour coming out of the interactions of market participants. Early models in this class include the famous Santa Fe Institute Stock Market model developed in the mid 1990s. This

nice historical summary by Blake LeBaron explores the motivations of this early agent-based model, the first of which was to include a focus on the interactions among market participants, and so go beyond the usual simplifying assumptions of standard theories which assume interactions can be ignored. As LeBaron notes, this work began in part...

... from a desire to understand the impact of agent interactions and group learning dynamics in a financial setting. While agent-based markets have many goals, I see their first scientific use as a tool for understanding the dynamics in relatively traditional economic models. It is these models for which economists often invoke the heroic assumption of convergence to rational expectations equilibrium where agents’ beliefs and behavior have converged to a self-consistent world view. Obviously, this would be a nice place to get to, but the dynamics of this journey are rarely spelled out. Given that financial markets appear to thrive on diverse opinions and behavior, a first level test of rational expectations from a heterogeneous learning perspective was always needed.

I'm going to write posts on this kind of work soon looking in much more detail. This early model has been greatly extended and had many diverse offspring; a more recent

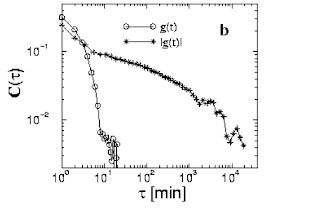

review by LeBaron gives an updated view. In many such models one finds the natural emergence of power law distributions for returns, and also long-term correlations in volatility. These appear to be linked to various kinds of interactions between participants. Essentially, the market is an ecology of interacting trading strategies, and it has naturally rich dynamics as new strategies invade and old strategies, which had been successful, fall into disuse. The market never settles into an equilibrium, but has continuous ongoing fluctuations.

Now, these various models haven't yet explained anything, but they do pose potentially explanatory mechanisms, which need to be tested in detail. Just because these mechanisms CAN produce the right numbers doesn't mean this is really how it works in markets. Indeed, some physicists and economists working together

have proposed a very different kind of explanation for the power law with exponent 3 for the (cumulative) distribution of returns which links it to the known power law distribution of the wealth of investors (and hence the size of the trades they can make). This model sees large movements as arising in the large actions of very wealthy market participants. However, this is more than merely attributing the effect to unknown fat tails in fundamentals, as would be the case with EMH based explanations. It starts with empirical observations of tail behaviour in several market quantities and argues that these together imply what we see for market returns.

There are more models and proposed explanations, and I hope to get into all this in some detail soon. But I hope this explains a little why I don't find the EMH based ideas very interesting. Being consistent with these statistical regularities is not as interesting as suggesting clear paths by which they arise.

Of course, I might make one other point too, and maybe this is, deep down, what I find most empty about the EMH paradigm. It essentially assumes away any dynamics in the market. Fundamentals get changed by external forces and the theory supposes that this great complex mass of heterogenous humanity which is the market responds instantaneously to find the new equilibrium which incorporates all information correctly. So, it treats the non-market part of the world -- the weather, politics, business, technology and so on -- as a rich thing with potentially complicated dynamics. Then it treats the market as a really simply dynamical thing which just gets driven in slave fashion by the outside. This to me seems perversely unnatural and impossible to take seriously. But it is indeed very difficult to rule out with hard data. The idea can always be contorted to remain consistent with observations.

Finally, another valuable comment:

David K. Waltz said...

In one of Taleeb's books, didn't he make mention that something cannot be proven true, only disproven? I think it was the whole swan thing - if you have an appropriate sample and count 100% white swans does not prove there are ONLY white swans, while a sample that has a black one proves that there are not ONLY white swans.

Again, I agree completely. This is a basic point about science. We don't ever prove a theory, only disprove it. And the best science works by trying to find data to disprove a hypothesis, not by trying to prove it.

I assume David is referring to my discussion of the empirical cubic power law for market returns. This is indeed a tentative stylized fact which seems to hold with appreciable accuracy in many markets, but there may well be markets in which it doesn't hold (or periods in which the exponent changes). Finding such deviations would be very interesting as it might offer further clues as to the mechanism behind this phenomenon.

NOW, for the question I wanted to pose. I've been doing some research on the history of finance, and there's something I can't quite understand. Here's the problem:

1. Mandelbrot in the early 1960s showed that market returns had fat tails; he conjectured that they fit the so-called Stable Paretian (now called Stable Levy) distributions which have power law tails. These have the nice property (like the Gaussian) that the composition of the returns for longer intervals, built up from component Stable Paretian distributions, also has the same form. The market looks the same at different time scales.

2. However, Mandelbrot noted in that same paper a shortcoming of his proposal. You can't think of returns as being independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.) over different time intervals because the volatility clusters -- high volatility predicts more to follow, and vice versa. We don't just have an i.i.d. process.

3. Lots of people documented volatility clustering over the next few decades, and in the 1980s Robert Engle and others introduced ARCH/GARCH and all that -- simple time series models able to reproduce the realistic properties of financial times, including volatility clustering.

4. But today I found several papers from the 1990s (and later) still discussing the Stable Paretian distribution as a plausible model for financial time series.

My question is simply -- why was anyone even 20 years ago still writing about the Stable Paretian distribution when the reality of volatility clustering was so well known? My understanding is that this distribution was proposed as a way to save the i.i.d. property (by showing that such a process can still create market fluctuations having similar character on all time scales). But volatility clustering is enough on its own to rule out any i.i.d. process.

Of course, the Stable Paretian business has by now been completely ruled out by empirical work establishing the value of the exponent for returns, which is too large to be consistent with such distributions. I just can't see why it wasn't relegated to the history books long before.

The only possibility, it just dawns on me, is that people may have thought that some minor variation of the original Mandelbrot view might work best. That is, let the distribution over any interval be Stable Paretian, but let the parameters vary a little from one moment to the next. You give up the i.i.d. but might still get some kind of nice stability properties as short intervals get put together into longer ones. You could put Mandelbrot's distribution into ARCH/GARCH rather than the Gaussian. But this is only a guess. Does anyone know?